Companies are facing technical and marketing pros and cons as they increasingly turn to cold-press CBD extraction as a way around novel food market limitations in the UK and Ireland.

Companies are facing technical and marketing pros and cons as they increasingly turn to cold-press CBD extraction as a way around novel food market limitations in the UK and Ireland.

The UK ingestible CBD product market is effectively now a closed shop following the publication of a final list of products linked to a credible novel food application submitted to the UK Food Standards Agency (FSA) for authorisation and with evidence of being present on the market on 13th February 2020.

However, the FSA has elected to consider ingestible CBD products made through cold press extraction as non-novel – meaning they can legally be introduced for sale in England and Wales without needing to wait for a novel food application to be approved. Authorities in Ireland take a similar view.

CBD is generally extracted using a solvent such as carbon dioxide (CO2), ethanol, or a hydrocarbon such as butane. Processed cannabis or hemp is exposed to a solvent which binds to the cannabinoids, which can be isolated. Other less common methods include technological innovations such as microwave-assisted extraction.

Physics vs chemistry

However, cold press extraction uses a physical approach rather than a chemical or technological one. Intense pressure is applied to the cannabis or hemp plant to release the oil that contains cannabinoids. The product is kept at lower temperatures, hence “cold”’ to prevent certain forms of degradation.

The resulting oil is already a spectrum product compared to a solvent extracted oil, where constituents such as terpenes and minor cannabinoids are also separated out or broken down and need to be added back in.

This forms the basis for much of the marketing surrounding cold-pressed oils. The reason cold-press techniques were not the industry standard from the get-go is that is simply that they cannot produce comparable levels of yield and efficacy compared to other extraction techniques.

This is because the process is non-selective. The same mechanism that results in a spectrum product also means cold-press extracts cannot match alternative methods in terms of yields of specific substances. Solvents bind to cannabinoids, meaning a higher percentage is drawn out.

In cold-press extraction, cannabinoids are not being isolated but rather the cannabis product is being separated into liquid oil and solid plant matter. The physics of a solid-liquid phase separation are simply far less selective, a problem further exacerbated by the lack of heat.

That lack also means the process results in non-decarboxylated cannabinoids, so most constituents will be the acidic precursor versions, such as CBDA, rather than CBD.

Contaminants necessitate further processing

To decarboxylate those acidic constituents, a producer would have to apply heat but this could destroy heat-sensitive compounds such as terpenes. Equipment such as a vacuum oven would be required to do this.

It should be noted that quite a few marketers of cold-pressed CBD products surveyed by CBD-Intel did not differentiate between CBDA and CBD content in the information provided on their cold-pressed CBD ingestible products, while those that did showed significantly higher CBDA than CBD content.

Issues also remain around other contaminants slipping by, presenting the need for further processing, which is not usually discussed.

There are techniques available that might improve the overall yield of cold-press extraction. Feed material like hemp can be pre-treated with certain enzymes to increase the output from cold-pressing techniques. However, this approach has not really been explored outside research.

For the time being, solvent-based approaches are still widely embraced in the industry for their affordability and efficiency, particularly when scaled, despite the issues they bring in terms of product degradation, longer extraction times, and potential environmental harms.

What This Means: In the UK and the Republic of Ireland the trump card on cold-press or other extraction methods remains regulation.

If a cold-pressed product does not need the time-consuming and expensive process of a novel food application and can immediately be brought to market or modified in response to consumer feedback, while competitor products must wait to enter or change, this far outweighs cold press’s disadvantages of yield, non-decarboxylated forms and potential contaminants.

It is no surprise, then, that an increasing number of brands in the UK look to be turning to cold-press extraction methods. Particularly when with a little bit of marketing fudging, issues can be obscured and products produced using the method can be touted as “more natural” or “closer to the plant”.

– Clayton Hale CBD-Intel contributing writer

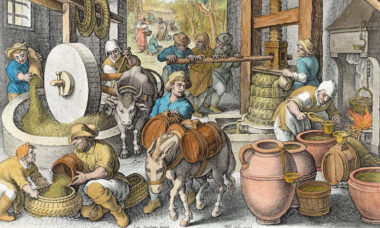

Image: Jan van der Straet